|

Custom Search

|

|

Infectious Disease Online Pathology of Leprosy

|

|

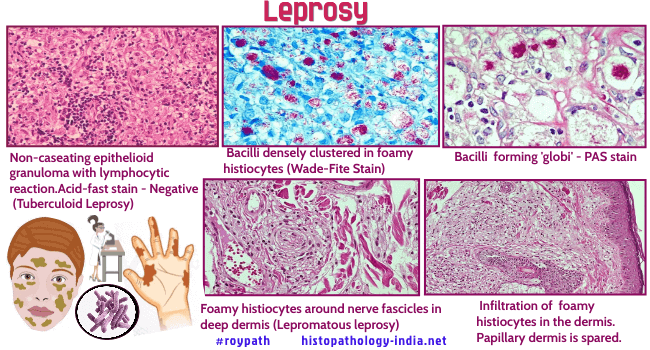

Leprosy (Hansen’s disease) is a slowly progressive, chronic infectious disease caused by the bacillus Mycobacterium leprae. It is a very serious, multilating and stigmatizing disease in many parts of the world and early diagnosis and therapy is the most important strategy for its control. It is highly infective, but has low pathogenicity and low virulence with a long incubation period. The geographical distribution of leprosy has varied greatly with time and it is now endemic only in tropical and subtropical regions such as India and Brazil. It affects the cooler part of the body, especially the nasal mucosa, upper respiratory tract, peripheral nerves, testes, the skin of the ears, and the anterior segment of the eyes. It is of historical interest that leprosy was the first reported bacterial pathogen of mankind. For centuries, leprosy was widespread in Europe and England. Indeed in 1873 Hansen first saw the lepra bacillus in fresh mounts of scrapings from a leproma of a Norwegian patient. A few patients still acquire leprosy in temperate regions, such as United States and Europe, but most patients in temperate climates are immigrants who were infected elsewhere. Lepra bacilli are slender, weakly acid-fast rods. All attempts to culture the organism have failed or are unsubstantiated. Lepra bacilli multiply in experimental animals at sites with temperature below that of the internal organs, such as the foot pads of mice, and the ear lobes of hamsters, rats, and other rodents. Naturally acquired leprosy has now been recognized in armadillos (Louisiana and Texas), in a chimpanzee trapped in Sierra Leone and in a man-gabey monkey captured in Nigeria. Lepra bacilli have been experimentally transmitted to armadillos, whose susceptibility is related, in part, to their low central body temperature (32 - 35C). Leprosy exhibits a variety of clinical and pathologic features. The lesions vary from the small, insignificant, and self-healing macules of tuberculoid leprosy to the diffuse, disfiguring, and sometimes fatal lesions of lepromatous leprosy. This extreme variation in the presentation of the disease is not fully understood, but is probably related to differences in immune reactivity. Ninety-five percent of all people have a natural protective immunity and are not infected even through inmate and prolonged exposure. In the susceptible 5% who may develop symptomatic infections, a broad immunologic spectrum ranges from anergy to hyperergy. Anergic patients (i.e. those with little or no resistance) have lepromatous leprosy, whereas hyperergic patients (those with high resistance) develop tuberculoid leprosy. "Borderline" leprosy is the term applied to the broad middle ground into which most patients fall. Patients with lepromatous leprosy have nodular and diffuse infiltrates of the skin, eyes, testes, nerves, and organs of the reticuloendothelial system. The most severe involvement of the skin is in exposed areas. The nodular distortions of the face are called “leonine facies”. The infiltrates are composed of tumour-like accumulations of histiocytes, each histiocytes containing enormous numbers of lepra bacilli. The epidermis is stretched thinly over the nodules, and beneath it is narrow, uninvolved "clear zone" of dermis.

Rather than destroying the bacilli, the phagocytic cells appear to act as microincubators. Unchecked, these infiltrates expand slowly to distort and disfigure the face, ears, and upper airway and to destroy the eyes, eyebrows and eyelashes, nerves, and testes. Oral manifestations usually appear in lepromatous leprosy and occur in 20-60% of cases. They may take the form of multiple nodules (lepromas) that progress to necrosis and ulceration. The ulcers are slow to heal, and produce atrophic scarring or even tissue destruction. The lesions are usually located on the hard and soft palate, in the uvula, on the underside of the tongue, and on the lips and gums. There may also be destruction of the anterior maxilla and loss of teeth. The diagnosis, based on clinical suspicion, is confirmed through bacteriological and histopathological analyses, as well as by means of the lepromin test (intradermal reaction that is usually negative in lepromatous leprosy form and positive in the tuberculoid form). There is a predominance of suppressor CD8+ over CD4+ T lymphocytes. Lepromatous tissues are rich in the mRNAs of the TH2 cytokines. The loss of ability to kill bacteria appears to be specific for Mycobacterium leprae. Patients with lepromatous leprosy are not unusually susceptible to opportunistic infections, cancer, or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and maintain delayed-type hypersensitivity to candida,Trichophyton, mumps, tetanus toxoid, and tuberculin. Those who are untreated may die of asphyxiation from an obstructed airway or from secondary amyloidosis. The other end of the spectrum is represented by patients with tuberculoid leprosy, a condition characterized by a single lesion or very few lesions of the skin. The hypopigmented macule, with a raised "infiltrated" border, may be hypesthetic or anesthetic. The lesion expands slowly over a period of months or years, and then gradually heals, although the hypesthesia or anesthesia remain. Microscopically, the tuberculoid lesion is a dermatitis characterized by discrete noncaseating granulomas in the dermis. The granulomas are composed of epithelioid cells and Langhan’s giant cells and are associated with varying numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells. The diagnosis of tuberculoid leprosy is often difficult on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) due to the absence of demonstrable nerve destruction. S-100 protein is superior to hematoxylin and eosin H&E in identifying nerve fragmentation. It also aids the differential diagnosis of tuberculoid leprosy. Cutaneous nerves, including the small dermal nerve twigs, are eventually destroyed by the bacilli, which accounts for the sensory deficit. Patients with borderline leprosy have an endless variety of features of both lepromatous and tuberculoid leprosy. The term "indeterminate" leprosy is used when the biopsy sample is taken from a lesion that is so early in the course of the disease that the cellular response does not reveal the type of leprosy. Thus, "indeterminate" lesions may heal spontaneously or progress to either lepromators or tuberculoid forms. The most commonly used drugs, dapsone, rids the lepromatous patient of lepra bacilli in 4 to 6 years, but it must be continued indefinitely. Dapsone - resistant strains of Mycobacterium leprae have developed, and multidrug regimens are now often used.

|

|

|