|

Custom Search

|

|

Infectious Disease Online Pathology of Typhoid Fever

|

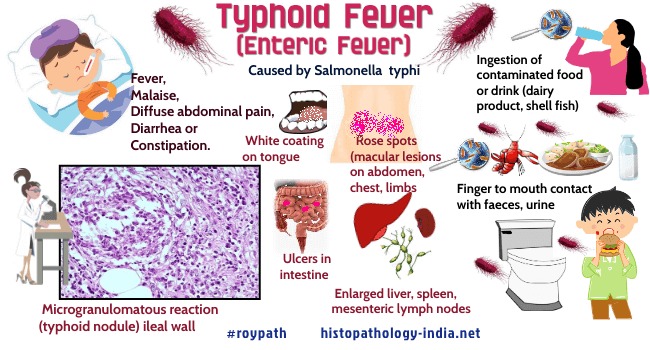

Typhoid fever is an acute systemic illness caused by motile, gram-negative bacilli of the genus Salmonella usually Salmonella typhi.Typhoid fever, also known as enteric fever, is a potentially fatal multisystemic illness caused primarily by Salmonella typhi bacteria ( a motile, gram-negative bacilli ).The organisms are gram-negative, flagellated, noncapsulated, non-sporulating, facultative anaerobic bacilli, which have characteristic flagellar, somatic, and outer coat antigens.Typhoid fever, the most serious human salmonellosis, is characterized by prolonged fever, bacteremia and multiplication of the organisms within mononuclear phagocytic cells of the liver, spleen, lymphnodes, and Payer’s patches.Humans are the only natural reservoir for Salmonella typhi, and typhoid fever therefore must be acquired from convalescing patients or from chronic carriers- specially older women with gallstones or biliary scarring, in whom Salmonella typhi may colonize the gallbladder or biliary tree. Mode of infection: Typhoid fever is spread primarily through ingestion of contaminated water and food (especially dairy products and shellfish), and much less commonly by direct finger-to-mouth contact with faeces, urine, or other secretions. Although concentrations of Salmonella typhi in the water or food may be too low to cause infections, the organisms may proliferate sufficiently when environmental conditions are favourable to cause infection. Shellfish in contaminated water filter large volumes and concentrate the microbial content, a process that accumulates enormous doses of S. typhi in raw shellfish. Urine from patients with pyelonephritis can be a significant source of Salmonella typhi. Typhoid fever has become rare in countries with modern control of sewage and of water and milk supplies. Throughout history of armies and refugees have been especially susceptible. Stages of infection: Click on the imageUntreated typhoid fever progresses through the following five stages: Incubation (10-14 days); Active invasion/bacteremia (1 week) ; Fastigium (1 week); Lysis (1 week) and Convalescence (several weeks). Following ingestion, bacilli must first survive gastric acid. Thus, patients who ingest antacids, have had a gastrectomy, or have low gastric acidity for other reasons require fewer organisms for infection. Bacilli that survive gastric acidity attach preferentially to the tips of villi in the small intestine, onvade the mucosa immediately, or multiply in the lumen for several days before penetrating the mucosa. The bacilli then pass to the lymphoid follicles of the intestine and the draining mesenteric lymph nodes. Some organisms pass into the systemic circulation and are phagocytosed by the reticuloendothelial cells of liver and spleen. Bacilli invade and proliferate further within the phagocytic cells of the intestinal lymphoid follicles, mesenteric lymph nodes, liver, and spleen. During this initial incubation period, therefore, the bacilli are primarily sequestered in the intracellular habitat of the intestinal and mesenteric lymphoid system. Eventually the bacilli are released from the reticuloendothelial cells, pass through the thoracic duct, enter the blood stream, and produce a primary transient bacteremia and clinical symptoms. During this active invasion/bacteremic phase, bacilli disseminate to and proliferate in many organs, but are most numerous in organs that possess significant phagocytic activity, namely liver, spleen and bone marrow. The Peyer’s patches of the terminal ileum and the gall bladder are also hospitable sites. Bacilli invade the gall-bladder from either blood or bile, after which they reappear in the intestine, are excreted in the stool, or reinvade the wall of the intestine. Clinical presentation: Clinically, the patients develop fever, diarrhea or constipation, vomiting, abdominal distention, myocarditis, splenomegaly, leukopenia, and mental changes. In some patients green yellow liquid "pea soup" diarrhea may occur. The patient’s temperature follows a characteristic pattern. It remains normal during the incubation period, undergoes daily stepwise elevations during active invasion, remains high during fastigium, falls slowly (with fluctuations) during lysis, and remains normal during convalescence. During the bacteremic phase, patients typically have a spiking afternoon fever that increases daily (up to 105C) before stabilizing in the second or third week of illness. The high fever is often associated with prostration and delirium. In the final phase, usually 3 to 5 weeks after onset, the patient is febrile and exhausted, but recovers if there are no complications. Infection of Peyer’s patches leads to lymphoid hyperplasia, which can resolve without scarring or can progress to capillary thrombosis, with necrosis and ulceration. Salmonella typhi in the blood during the second or third week of illness initiate prolonged bacteremia, often heralded by the transient appearances of "rose spot"-macular lesions on the limbs, lower abdomen, and chest that resemble petechial hemorrhages, but are actually foci of hyperemia (capillary atony). Microscopically, the macular lesions are edematous and infiltrated with histiocytes- an appearance that reveals that they are sites of bacterial localization and toxic injury. Bacteria are seeded to the organs, including, spleen, liver, kidneys, and gallbladder, and chronic cholecystis may be established. Bacteria shed from the gallbladder reinfect the intestine, producing a tender abdomen and diarrheal disease, and they may also produce hepatosplenomegaly. Complication: The most frequent and severe complication is intestinal perforation with peritonitis. Other problems are bleeding and thrombophlebitis, usually of the saphenous vein, cholecystitis, pneumonia and focal abscesses in various organs and tissues. The mortality from these complications ranges from 2% to 10% without treatment. About 20% of untreated convalescent patients relapse. Diagnosis: Success of cultivation of salmonella varies with stage and "tissue" (blood, urine, or stool). Cultures of blood may be positive during incubation and are usually positive during active invasion and fastigium ; they are usually negative during lysis and convalescence. Culture of urine and stool grow salmonella less frequently, but usually become positive toward the end of fastigium. Stool cultures remain positive until late convalescence. The Widal agglutination test, using H (flagellar) or O (somatic) antigens, becomes positive 10 or more days after onset, titers continue to rise into convalescence. Pathological features: The earliest pathologic changes are in the stages of bacterial attachment and penetration. Bacteria are firmly attached to intestinal epithelium with an accompanying degeneration of the brush borders. Later as the salmonellae pass to lymphoid follicles of the intestine, there is diffuse enterocolitis and hypertrophy of Peyer’s patches. This is followed by necrosis of intestinal and mesenteric lymphoid tissues, focal granulomas in the liver and spleen, and characteristic mononuclear inflammatory cells ("typhoid nodules") in many organs. Typhoid nodules are primarily aggregates of altered macrophages ("typhoid cells") that phagocytose bacteria, erythrocytes and degenerated lymphocytes. These nodules also contain plasma cells and lymphocytes, but not typically neutrophils. The most common sites for typhoid nodules are the intestine, mesenteric lymph nodes, spleen, liver, and bone marrow. Less commonly, the kidney, testes, and parotid gland are affected. Although the pathologic changes of typhoid fever may not correlate precisely with the clinical stages, certain patterns are characteristic. During the incubation stage there is a mild enteritis, mesenteric lymphadenitis, and hyperplasia of intestinal lymphoid tissue, primarily of Peyer’s patches of the ileum and solitary lymphoid follicles of the cecum. The lymphoid hyperplasia may resolve or may progress to capillary thrombosis. Thrombosis causes the adjoining intestinal mucosa to enlarge during the phase of active invasion and then become necrotic. This process gives rise to the characteristic lesions, which are elevated 0.1 to 0.4 cm above adjacent mucosa. While bacilli continue to proliferate, dying bacilli release endotoxins that cause toxemia, beginning during invasion and becoming maximal in fastigium. The necrotic mucosa sloughs, usually during lysis,producing ulcers that conform to Peyer’s patches and are concentrated along the antimesenteric border. The ulcers may bleed or perforate, usually during lysis. Most perforations are near the ileocecal valve, measure less than 1 cm across, and lead to peritonitis. Interestingly, these areas become repopulated with lymphoid cells and heal without scarring. During active invasion the mesenteric lymph nodes enlarge and develop typhoid nodules, focal hemorrhages, and necrosis, changes which resemble those in the intestinal lymphoid tissue. The spleen becomes large and hyperemic and microscopically shows typhoid nodules in the red pulp. The hyperplastic white pulp exhibits areas of focal necrosis. The enlarged liver displays sinusoids lined with swollen Kupffer’s cells and histiocytes. Focal necrosis of liver cells is common. The lack of neutrophils in typhoid fever is conspicuous. The intestinal ulcers and focal areas of necrosis, are bounded only by chronic inflammatory cells, and the patient is actually leukopenic. Toxemia may cause other complications, including ileus ; mild fatty liver; a flabby heart with dilated ventricles, vacuolization of cardiac myocytes, and cardiac arrhythmia that may cause sudden death; mild interstitial pneumonitis ; swelling and degeneration of the proximal tubular epithelium of kidney; "ring" hemorrhages in brain; capillary microthrombi ; and degeneration of skeletal muscles. During convalescence, the intestine returns to normal, with minimal scarring of the mucosa. Adhesions are rare. Typhoid nodules in various organs are resorbed without distortion of the architecture. The capsule of the spleen, however, may become fibrotic, giving the appearance of “sugar coating”. Skeletal muscles regenerates and toxic changes of heart disappear. Treatment: The most widely used antibiotic for typhoid fever is chloramphenicol. However, this drug does not reduce the relapse rate, and convalescent excretors and chronic carriers are not cured. Moreover, some strains of S typhi are resistant, and chloramphenicol may cause aplastic anemia. Other effective antibiotics (some without these disadvantages) are ampicillin, amoxicillin, and trimethoprim-sulfametholoxazole.

|

|

|